Rich Davies is Ark’s Director of Insight. He is responsible for bridging the gap between the organisation’s data and action. He advises senior leaders on strategic issues and works to ensure that all Ark leaders, teachers and students can make data-informed decisions. He has overseen the development of Ark’s award-winning data analytics systems and has led reviews of assessment, curriculum, destinations and many other key areas.

Rich Davies is Ark’s Director of Insight. He is responsible for bridging the gap between the organisation’s data and action. He advises senior leaders on strategic issues and works to ensure that all Ark leaders, teachers and students can make data-informed decisions. He has overseen the development of Ark’s award-winning data analytics systems and has led reviews of assessment, curriculum, destinations and many other key areas.

Introduction

This blog series explores all aspects of ‘curriculum’, but my posts specifically focus on macro-curriculum – the subjects and qualifications we teach, their availability to different students, and the resource we invest in teaching them.

My objective is to help make schools’ macro-curriculum decisions more explicit, as well as informing them with data where possible.

The three types of macro-curriculum decision I explore in these posts are:

- Student entitlement

- School breadth

- Lesson context

You can read my previous posts on ‘student entitlement’ decisions here and ‘school breadth’ decisions here.

3. Lesson context

‘Lesson context’ decisions determine the amount and level of content that can be delivered in lessons. However, they do not include deciding on the actual lesson content itself, which will be addressed by John Blake and the Ark Curriculum Partnerships team elsewhere in this series.

How many hours should each subject be taught for?

– If this should differ by subject, how?

This data is not collected at a national level, but we have been seeking to better understand how our own schools align and differ along this dimension. The time available to teach any particular subject is obviously influenced by the duration of the school day, the time reserved for non-lesson activity, as well as the number of different subjects on offer (i.e. ‘school breadth’), but this still leaves schools to decide how they allocate teaching time between each subject area.

During KS3 in our schools, English typically gets the most lesson time, while Maths, Humanities and Sciences also get a substantial share of timetabled hours. Other subject areas tend to get a few hours per week, depending on the school and subject. The pattern is mostly similar in KS4, except that Science tends to receive additional hours, often in exchange for ‘non-core’ subject areas.

In terms of variation between our schools, we see the greatest range in terms of English hours, which often include additional time for reading, literacy etc. This variation reflects the different literacy levels seen across our incoming cohorts, which is often linked to levels of EAL as well as economic disadvantage. Variation is also seen across other subjects, though the range is usually only +/-30 mins between different schools. However, even relatively small variations can add up over time, which impacts the total amount of content that can be covered (and re-covered) between different subjects and schools.

At Primary level, English and Maths predictably take the lion’s share of timetabled hours in our schools, with Science, Humanities and PE also receiving multiple hours per week. Other subject areas tend to occupy fewer lessons per week, though the specifics vary based on schools’ individual priorities and cohort needs. As with KS3/4, this variation inevitably impacts the total amount of content that can be covered within each subject at each school. This obviously poses a challenge in terms of network alignment, which I will revisit later in this post.

How many students should there be within a teaching group?

– If this should differ by subject, how?

Once again, this data is not collected nationally. However, our own internal analysis suggests that Primary and KS3 class sizes are typically determined by school-specific cohort sizes and funding-rates, rather than subject-specific differentiation. The main exception to this is when ‘supplementary’ subjects (e.g. literacy, reading or numeracy) are delivered to targeted groups of students, while their peers remain in larger classes. Meanwhile, KS4 and KS5 class sizes are also influenced by the number of students that opt for different subjects.

Several research studies have looked at the impact of class sizes, and the EEF’s summary suggests that small variations in class size do not have a significant impact on outcomes. In other words, unless you can reduce class sizes to below ~20 students (which is economically challenging for most schools), it is difficult to realise any potential benefits.

How should the members of each teaching group be determined?

– e.g. mixed ability/setting?

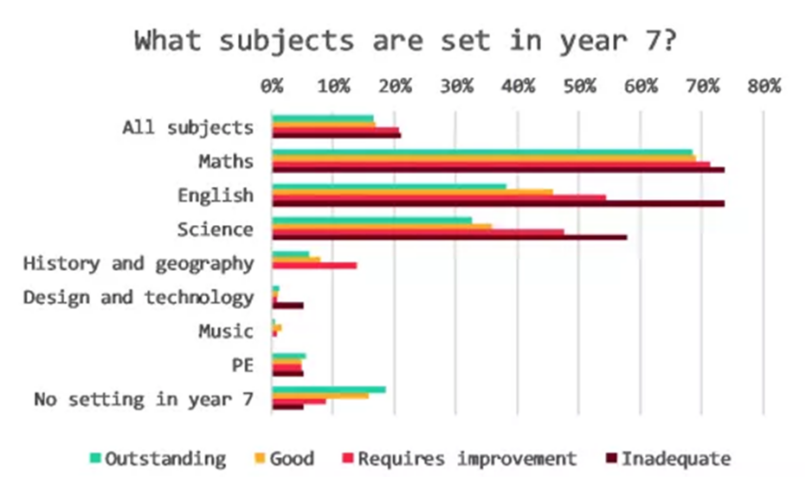

Despite being the source of much national debate, this data is again not captured nationally. However, Teacher Tapp research suggests that 15-20% of schools set all subjects from KS3. Differentiating by subject, >80% set for Maths, but closer to ~50% set for English and Science.

Source: Teacher Tapp – November 2017 (Chart 5)

Interestingly, they also found that schools with higher Ofsted ratings are less likely to set – especially for English and Science. However, it’s unclear which way around the causation works in this case (i.e. we don’t know if schools rated higher because they don’t set or if higher rated schools are more likely to have intakes that don’t warrant setting).

Research into setting has mostly been inconclusive, but the EEF’s best practice guidance now advises against streaming (i.e. setting all classes in tandem without differentiating by subject) and promotes attainment-based grouping within mixed-attainment classes.

Should all teachers align with school/network on curriculum architecture?

– If this should differ by school or subject, how?

This is another live debate which does not yet have much data to back one approach over the other. Based on anecdotal evidence, it’s probably reasonable to assume that the majority of teachers do not currently align with their colleagues on design architecture (e.g. curriculum maps, knowledge definitions etc) and/or delivery architecture (e.g. lesson plans, teaching resources, student resources etc).

In KS4 and KS5, signing up with the same exam boards might lead to some degree of alignment on design architecture, but individual teachers are still self-generating a lot of delivery architecture by converting these exam specifications into medium-term and lesson plans. Below KS4, there is likely even less alignment – with the possible exception of the schools that participate in curriculum and professional development programmes like Mathematics Mastery or English Mastery.

From Ark’s perspective, we are in favour of alignment of curriculum and assessment architecture, not just within each school but, where possible, across the network. John Blake and the Ark Curriculum Partnerships team will explain this rationale much more throughout the remainder of this series, but our pro-alignment positioning is mainly driven by a desire to leverage deeper expertise while minimising the duplication of teacher workload. Furthermore, from an assessment perspective, curriculum alignment enables comparing like with like, which is a pre-requisite for any data point to be considered meaningful.

However, there is clearly a challenge here if there is significant variation between schools in terms of the total hours allocated to each subject. One theoretical remedy might be for a network to centrally mandate the hours for each subject, but this is not the approach that we at Ark have taken. Instead, the content being developed by Ark Curriculum Partnerships reflects a recommended ‘base’ time allocation, but with enough tolerance built in to allow for some inter-school variation.

So what?

This final set of macro-curriculum questions does not enjoy the same level of national data transparency as the previous two. As such, it is difficult for schools to determine where they sit along the national spectrum for these topics. Nevertheless, schools still need to ask themselves “what structures should we put in place to influence what’s delivered in each lesson?”. Hopefully, more benchmarking information will be made available over time in order to better inform these decisions, but in the meantime, schools should look to learn as much as possible from each other, while accounting for differences in local context.

At Ark, we now use the questions covered by these three posts as part of an annual review of each school’s macro-curriculum. While there are no centrally mandated answers to these questions, we do use network and national benchmarks in order to challenge and support the decisions made by each school.

Whether you are thinking about ‘student entitlement‘, ‘school breadth‘ or ‘lesson context’ – many different macro-curriculum decisions are potentially valid, as long as your school is clear about what you’ve decided and why you’ve decided it.